Steve Jordan looks at some English expressions and why we use them.

Picture the scene. Three chaps are sitting in a bar, me and two others who should best remain nameless (but let’s just call them Nick Flaxman and John Mitchell from Pluscrates) to preserve their good names. It’s been a long and productive day and a similarly long and enjoyable night. The time is 2.00am. Most sensible people have retired but the attraction of just one more Jack Daniels is more than the weakened mind can bear. We agree that we are all ‘three sheets in the wind’ and from there a whole new thread of conversation blossoms.

What are these crazy expressions we all use in English every day? They are meaningless, yet we all understand them. Where do they come from? It was likely that our three musketeers would see the sun rise before they found a conclusive answer.

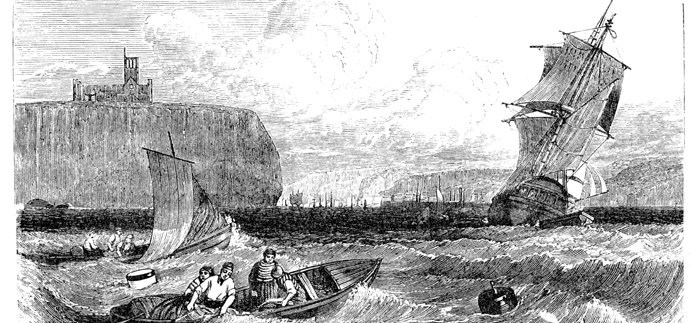

Many of our favourite expressions come from Britain’s illustrious maritime past. A ‘sheet’ for example is not something to cover a bed but a rope used to trim a sail. Let the sail fly and the sheet waves around in a most alarming way. ‘Three sheets in the wind’ would indeed be a wayward sight, not dissimilar to watching us make our way back to our hotel rooms, no doubt.

‘Sailing close to the wind’ is another maritime expression meaning ‘to take a risk’. A ship cannot, of course sail directly into the wind so, to make headway against it, it must sail as close as possible: sail too close and the ship stalls – a risky business, especially in confined waters. If you are sailing as close to the wind as possible, you could be said to be sailing ‘by’ the wind. To do so your sails will be pulled in as tight as possible. Bear away from the wind and you let your sails out making the ship look much larger. Therefore, to sail ‘by and large’ is to sail almost close to the wind – more or less. A ship making way upwind would be ‘tacking’. To be ‘on the right tack’ therefore, means to be on the tack that will most quickly take you to your destination: an expression widely used in business.

‘Swinging the lead’ was a very important job on a ship. Before science invented echo sounders someone would sit on the side of the ship and drop a lead weight attached to a notched rope into the water and would give the navigator a continuous commentary on the depth of water under the ship. Important it might have been but, by comparison to some other jobs on board, it wasn’t physically demanding. So, to ‘swing the lead’ became an expression meaning to get out of hard work.

‘Between the devil and the deep blue sea’ is another nautical expression that has nothing to do with the occult. The Devil is the part of a ship where the upper deck and the ship’s side join. To be between it and the water means you’ve just fallen overboard and were, almost certainly, about to face a damp death. ‘Between Hell and high water’ probably comes from the same source.

There was a time when women were allowed on ships to help keep the chaps entertained. Of course all the sailors had to be up and about on the call of ‘turn to’ but the ladies could have a lie in if they wished. The officer in charge of rounding up the crew would, therefore, ask the lump in the bunk to ‘show a leg’. If it was obviously female, she could sleep on.

Of course this mixing of men and women on board had inevitable consequences. If a child was born on a ship the master had to record the birth. The name of the mother was never in doubt but the choice of father was extensive. So the old man would just write in the log ‘son of a gunner’ or ‘son of a gun’, to mark the happy event.

Perhaps the best known and probably most apocryphal nautical expression is, perhaps surprisingly, to ‘freeze the balls off a brass monkey’. The expression is nothing to do with male genitals or our ancestral friends. Iron canon balls were stacked on ships on brass pyramid-shaped frames called monkeys. As we all know from our science lesions at school, the coefficient of linear expansion of brass is greater than that of iron. When it got very cold, the brass would shrink more than the iron and the balls would fall off. It had to get pretty chilly though.

There are many more idioms that come from the sea, too many to mention here, but one that doesn’t is, strangely, ‘to spoil the ship for a ha’porth of tar’. This is a farming expression and refers to sheep not ships. Sheep get foot rot and farmers put tar on their feet to keep out infection. Not enough tar and the sheep could be spoiled. Being ‘tarred with the same brush’ comes from the same source, meaning to be alike or from the same flock.

I particularly like to ‘let the cat out of the bag’. I suppose it’s in my nature as a journalist. Market stall-holders used to sell live animals. Some rogue traders would put a cat (which was cheap and plentiful) in a bag and sell it as a much more wholesome pig. Only when the unsuspecting purchaser got home would they let the cat out of the bag and discover that they had been duped. To be ‘sold a pig in a poke’ comes from the same source. History doesn’t tell us what happened when the customer returned to register his complaint.

And finally, people used to use pewter drinking vessels and plates more than they do today. Pewter contains lead. One symptom of lead poisoning is that the sufferer’s bodily functions slow down until they appear to be dead. So, the family would lay them out on a slab and see if they woke up. They would hold a ‘wake’. Despite this precaution many were buried alive as proved by the scratch marks on the inside of exhumed coffins. A solution was to attach a piece of string to the hand of the occupant at one end and a bell, outside the coffin, on the other. If the bell rang the family would dig up uncle Albert. He would have been ‘saved by the bell’. Brilliant!