On 26 September, 2014, The Mover was invited to witness the inaugural flight of a revolutionary new concept in long distance transport that could solve the problem of delivering household goods to remote locations: the VV-Plane. Here is Steve Jordan’s take on what could be the most dramatic shift in transport since the invention of the railways.

Every international moving company has at some time struggled with deliveries to remote regions. Magazines such as The Mover revel in stories of containers being delivered, against the odds, on home-made rafts, by helicopter, or by intrepid drivers braving some of the world’s most dangerous roads to reach the interiors of South America, Africa, China or the frozen wastelands in Canada or Russia. But a new invention just might make these type of deliveries, not just of personal effects but of general cargo, as common as a Waitrose delivery van.

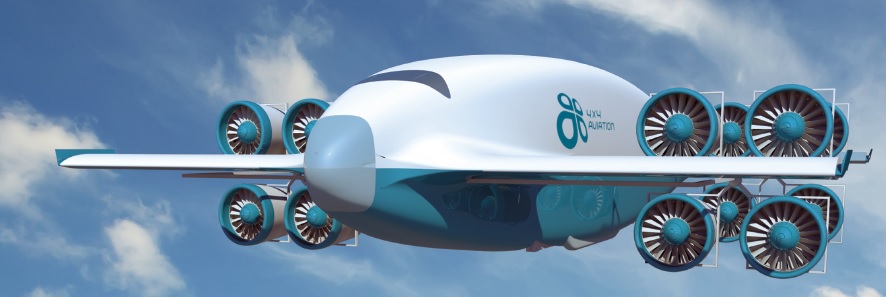

It is the brainchild of engineer, inventor and entrepreneur Thorsten U. Reinhardt who, through his company 4 x 4 Aviation, has taken a completely new look at the way in which these deliveries are made and has invented a method that he believes will be cheaper, faster, more practical and safer than a truck.

Thorsten came up with the idea when he was living in Bolivia, a landlocked country. Here, he said, the cost of the most basic goods is 50% higher than in Europe despite heavy government subsidies. Goods can be transported easily by ship to the nearest port, but it’s what happens from there that costs the money and takes the time.

Thorsten came up with the idea when he was living in Bolivia, a landlocked country. Here, he said, the cost of the most basic goods is 50% higher than in Europe despite heavy government subsidies. Goods can be transported easily by ship to the nearest port, but it’s what happens from there that costs the money and takes the time.

To solve the problem, Thorsten has invented a new type of aircraft. Anyone who remembers Gerry Andersen’s Thunderbird 2 will be familiar with the idea. It’s a vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) craft that accommodates, within its fuselage, a standard 20ft container. The plane lands on top of the container, locks it in place, and delivers it directly to its location without worrying about the dilapidated (or non-existent) infrastructure below. No runways, no terminals. It’s a simple idea, some may say an obvious one, but there is some pretty clever technology going on behind the scenes to make it work.

At the heart of the concept is a revolutionary propulsion system invented by 4 x 4 Aviation that is also attracting the attention of some of the major car manufacturers. It’s a hybrid system that uses a combustion engine to power a generator that stores its energy in batteries in the form of a pressure vessel that, in turn, powers electric turbines. Software, also developed by 4 x 4 Aviation controls the power units through micro-controllers with few mechanical components: that’s what makes the system unique. Each VV-Plane has 16 engines operating in clusters of four. Clusters of small engines are recognised as being more efficient than single large engines (a principle that is common throughout industry for computers, heat exchangers, separators, etc.).

Thorsten says that he requires a meagre £3.5m to complete the development work and build the full size prototype. He believes that this will be achievable within three years of securing the funding. Questioned about the modest funding requirement Thorsten said: “The thought process has already cost more than £2m. The difficult part is knowing how to do it. That’s where the funding has already gone. I now know how to do it. That is why I only need an additional £3.5m.”

Once the design is perfected and proven he intends to allow planes to be built, essentially from kits, locally to where they are needed benefiting from local government finance. “Because there are very few mechanical parts it will be possible for these developing countries to manufacture the VV-Planes themselves while we support them technically. We are looking to produce at least 30 aircraft a month initially in this way.”

Each aircraft will have an operating range of 3,300km at an average speed of 300kmh. They will each cost approximately £380,000 and have an operating lifespan of 20 years. This compares favourably with the cost of buying and running trucks. They will not need pilots. Maintenance costs will be low.

One potential problem area is payload. The first craft will be able to carry a container weighing no more than seven tonnes which gives a payload of around five tonnes. This might be a problem for some industries, but for movers, it’s ideal. Most household goods containers would have a net weight of no more than three tonnes so it is possible for the removal of household goods to be one of the first key applications for this new technology. Thorsten also has plans for the development of lightweight containers that would increase the payload but reduce the intermodal flexibility.

The test flight was successful although it was only of a small-scale model that rose a foot or two off the tarmac at Lydd airport in Kent, fluttered around a little, and landed again – twice. But it did demonstrate the principle. Some will read this article and scoff. Why not use a helicopter or an airship? Well, both are much more expensive to build and require highly trained pilots. Some will say it’s a crackpot idea that will never work. Well, maybe. But those people should remember that those are almost the exact words that were said to Frank Whittle only a few decades ago.

The test flight was successful although it was only of a small-scale model that rose a foot or two off the tarmac at Lydd airport in Kent, fluttered around a little, and landed again – twice. But it did demonstrate the principle. Some will read this article and scoff. Why not use a helicopter or an airship? Well, both are much more expensive to build and require highly trained pilots. Some will say it’s a crackpot idea that will never work. Well, maybe. But those people should remember that those are almost the exact words that were said to Frank Whittle only a few decades ago.

We live in a world that is changing more rapidly now than ever before and that acceleration will continue. A visitor to our world from only 20 years ago would hardly recognise it in terms of technology. If Thorsten is right, and he gets the backing he needs, we could easily be on the threshold of a transport revolution that will change the way goods are moved around the world and affect the lives of millions of people especially those who currently live in its most remote regions.

Don’t you think it’s exciting that the removals industry, for once, rather than struggling to shrug off its image as a bunch of semi-skilled humpers, might one day help to lead the way towards something extraordinary?

Engines

Combustion engine

He engine is a multi-staged (gas and steam) thermodynamic process machine built from off-the-shelf components that will be able to achieve 75% fuel efficiency with zero emissions.

Energy storage

Lightweight, double-walled pressure vessels allowing a fast charge and discharge of stored energy.

Reinhardt electric turbine

Internal blades connected to electric motors that function as outer runners and stators. Powered by an on-board generator or temporarily from batteries charged by the generator.

Facts & Figures

Wing span: 11.9 m

Fuselage: 15.2m x 2.7m x 3.5m

Empty weight: 3000kg

Max take-off weight: 10 tonnes

Maximum distance: 3,300km (2,050 miles)

Maximum speed: 330kmh

Fuel consumption: 65litres/100km

Cost: £380,000

Operational lifespan: 20 years

Images: From the top: CGI rendering of how the VV-plane will look: Thorsen U Reinhardt with the scale model at the test flight; the scale model about to leave the tarmac on its demonstration flight.

Click here to view the next Editor's pick